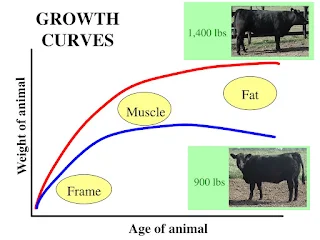

The conventional wisdom is that meat animals first grow their frame or bones. Then they add muscle. Then, when their muscles are mostly developed, calories go to growing fat.

Muscles are protein. Fat is...well, fat. Fat is flavor. Fat is energy.

High end buyers are looking for a 1/2" or thicker blanket of fat beneath the skin which they believe correlates to "marbling" and tenderness.

The first calories a calf consumes goes to "maintenance". Maintenance energy pumps the heart, moves the lungs in-and-out, moves the calf around the pasture, swats flies and keeps up body heat.

The larger the calf the more maintenance calories are needed.

The only calories that put money in my pocket are the calorie AFTER maintenance.

Palatability

|

| Concept drawing of the relationship between palatability, growth rate and the amount of standing forage. Time of cutting or grazing on left. |

The joker in the deck is the weather. If I have good rain I can move toward the left side of the chart and feed younger, more palatable pasture. The calves will eat more and it is more nutritious per bite so they grow faster.

If I don't have good rain then I can slow down the rotation by making them stay in each paddock longer. That gives each paddock longer to recover and (on average) the sward will spend more time in the middle of the growth-rate bell-curve.

If I have a very poor year for rain or if I was overly optimistic regarding stocking rates then it will be impossible to grow enough forage even for maintenance levels and I will need to supplement with grain or hay.

Because rains are not predictable, it is a great idea to have the ability to supplement because you can get into run-away acceleration of your herd. They will finish off a paddock and the next one is not quite ready but you move them anyway. The next paddock is even less ready and so on. By the time you get to the first paddock you are in trouble because all of those early jumps add up.

A few thoughts on forage species

Tall Fescue is a grass that people love to hate. Even in the best of times it is not very palatable. It is usually infected by a fungus (endophyte) that produces chemicals that repel insects (Yeah!!!) but can cause health problems in grazing animals (Boo!!!).Tall Fescue is tough. It can grow in very damp soils. It can grow in soils with low fertility. It resists baking sun and freezing cold.

Tall Fescue has one endearing quality: It "stockpiles" well. The clumps and blades stick up so it is easy for animals to find them beneath the snow and scrape the snow off of them. The blades don't degrade after severe freezes or months of drenching rain.

So even though most graziers will admit that Tall Fescue's palatability is "not that great" they are quick to agree that it is a niche player and the quality is "plenty good enough" to keep animals alive through the winter...even if they don't gain weight at an impressive clip.

Greg Judy has a great YouTube channel regarding this subject. Although he is in Missouri so his rotation plan requires some geographic tinkering - my climate and is closer to yours, I'm in PA, but the fundimentals are the same. I'm going to try mob grazing this coming spring instead of just transitioning from one paddock to the next I will be subdividing each paddock.

ReplyDelete