Nitrogen can be a complicated subject because "nitrogen" can mean four, very different things depending on context.

"Nitrogen" can mean N2 which makes up about 75% of the atmosphere. It is for all practical purposes inert and non-reactive.

"Nitrogen" can mean the various oxides of nitrogen formed when oxygen and nitrogen are heated up, often under pressure which occurs in internal combustion engines. Released to the atmosphere NOX are highly reactive and can contribute to smog, acid rain and allegedly lung damage.

"Nitrogen" as a plant nutrient can mean ammonia (NH3) or nitrates (HNO3 and assorted cations). For the most part, plants can only absorb the nitrates from the soil but soil bacteria are very good about converting NH3 to nitrates.

Finally, "nitrogen" can mean protein. As a rule-of-thumb, protein is about 16% nitrogen by weight. No nitrogen means no protein. Many of the chemicals important to photosynthesis and plant growth contain protein building blocks.

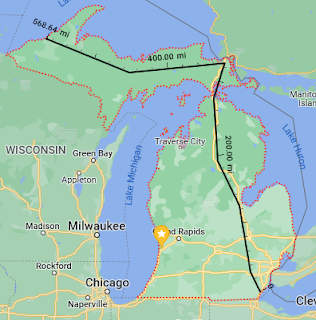

It also means that a shortfall of nitrates will have a dramatic impact on plant growth. Ironically, some of the plants we think of as carbohydrate producers are very heavy consumers of nitrates. No nitrogen means no chlorophyl. No nitrogen means that the plants will not fill their allotted space and capture the sunlight that is the energy source that creates carbs. In Michigan, potatoes and field corn are typically fertilized with 200 pounds of N per acre every year.

Another characteristic of nitrogen as a plant nutrient is that it is very mobile. It is easily leached out of the root zone. When in very high concentrations like manure or urine it can become ammonia which is very volatile and it can blow away in the breeze.

Nitrogen reminds me of the old joke "You don't buy beer, you rent it".

The good news

Air is 75% N2 which is almost inert. Almost but not totally inert.

There are some technologies that are accessible to people experiencing austere circumstances which cheerfully turn that N2 into nitrates.

There are some plants, clover for instance, that have the ability to host a species of bacteria that convert atmospheric, unfixed nitrogen into the kind of nitrogen that plants can use.

I am not going to pummel you with a hundred different versions of the technology. I am going to share ONE way to do it.

Feudal Compound

Suppose that you become a lifeboat for several families...perhaps sons and daughters and their families.

For the sake of argument, lets say that in addition to you and your beloved you have three young families join you "for the duration".

Casting about for a way to make this work, you decide that some variant of the feudal system will work.

Each of the four units is given 4000 square feet to manage as "garden". As lord-and-master of the estate, you mandate that 2000 square-feet is seeded to red clover in the fall after harvest and that the other 2000 square-feet be prepared for vegetables.

A pure stand of red clover can "fix" 250 pounds of nitrogen per acre under optimal conditions.

Since that 2000 square feet is in vegetation (perhaps year-old red clover) it is fenced off and chickens or other livestock is allowed to forage and beat-down the greenery.

Since matter is neither created or destroyed, very little of the "fixed" nitrogen does not pass through their digestive system and land back on the ground. The nitrogen that does not pass through their digestive system becomes protein in eggs and flesh and feathers.

By early spring, the clover patch will be eaten down to bare dirt. A few passes with a tiller once the soil is dry enough and you have pretty good nitrogen content for the years garden.

Year-by-year you alternate which 2000 square-feet are in clover or garden.

One variation

Small grains and red clover pair well. By itself, red clover produces more than enough nitrogen for the next years garden. Since you can tolerate less than 100% red clover intercepting sunlight, you could plant wheat, rye or another winter grain in the fall, frost seed the clover, harvest the grain in late-midsummer and then beat down the clover with chickens in fall-winter.

You probably want to seed the grain a little bit more thinly than if you were planting it alone.

A second variation

Some garden crops demand more nitrogen than others. Some crops produce all leaves and no crop when they have too much nitrogen.

The red clover year can be followed by a high user of nitrogen like corn, potatoes or cabbage.

Since matter is neither created or destroyed, the nitrogen that is not removed with the crop (corn leaves and stalks, potato tops, cabbage wrapper leaves) leave their nitrogen in the field.

The next year can be crops that like moderate nitrogen like peppers and tomatoes and beans and herbs.

Does it have to be red clover?

Nope. There are more than a dozen other choices. Red clover is a good starting point for nitrogen fixing plants in Michigan but it is not the only one. The seed is cheap and fairly easy to produce on-farm. It germinates rapidly and can choke out weeds. It is not excessively fussy about soil type or pH. It can have some issues as an animal feed but it does have a lot of protein.

What is wrong with mulch?

Two things to consider. You have to get it somewhere. If you were getting bags of leaves and grass-clippings from your neighbor then he might want to use them himself.

The other issue is a little bit more arcane. That mulch will also bring in extra potassium and phosphorous. Excessive amounts of those can cause some minor quality issues with your crop. For instance, excessive amounts of potassium will inhibit calcium uptake and transport. Lack of calcium is linked to a multitude of "soft fruit" type quality issues. Bottom line, the fruit will bruise and rot quickly.

A few words in parting

The crop-fallow-crop system will take a few years to tune in.

A family can starve to death in much less time than that.

Do not be too hard on yourself. A bag of nitrogen rich fertilizer like urea (46% N) can buy you time while you find your sea-legs.

2000 Calories: Labor

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)