This is a Geneva 210 rootstock that was planted in the spring of 2019 and allowed to grow. The cage that protected it from deer is in the background. The cage is 48" tall with a diameter of 10" and is made from light duty, 2"-by-4" welded wire fencing.

The rootstock is too shaggy. The shoots need to be stripped because they produce growth regulators that suppress the buds on the graft from growing.

Then I topped the rootstock with a pair of pruners.

Generally, the higher the scion is grafted, the more dwarfing the rootstock. Commercial orchards take steps to ensure that the graft union is at a uniform height through the entire orchard so they all exhibit uniform growth habits.

G.210 is a fairly vigorous rootstock so having a high graft is a bonus because I get more dwarfing. Furthermore, I ain't as young as I used to be so less bending over is good.

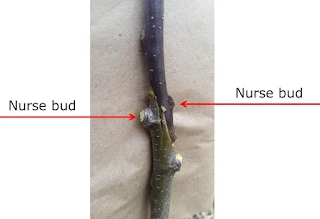

The scion also gets a nurse bud and for the very same reasons.

Now, you might look at the knob on the rootstock and observe, "Joe, that is the stub of a branch you removed...not a bud."

You are right. And there are latent buds buried in that stub.

Many grafting manuals list the angle of the slanting cut. Since I don't carry a protractor with me when field grafting, I make the length of ALL of my slanting cuts the width of my thumb. If the rootstock and scion are of approximately the same diameter then they should match up beautifully.

I have yet to lose my measuring tool while grafting although I have been known to cut it every once in a while.

This is the cut that makes people bleed. It is not necessary. Mostly, it serves as a convenience for the grafter because it dovetails to two pieces together and makes it easier to wrap.

Cecil Farris never used this additional, downward cut and he successfully grafted many difficult species.

This is what the two pieces look like when they are pushed together. If you look closely at the top, left you will see that the rootstock is not in full contact with the scion. Not a problem.

After wrapping with a rubber band. This is where the dovetail is convenient. The grafter simply does not have enough hands.

Rubber bands are fabulous for pulling the graft together if you stretch it a bit as you wrap it. I buy #32 and #33 rubber bands by the pound.

I suspect that a simple, spring-loaded clothespin could be that third hand and will investigate and report on the idea later.

After wrapping with masking tape. Splurge. Buy a new roll because it comes off the roll better.

The tape has three functions.

It shields the rubber band from UV light so it keeps the graft in compression long enough for it to heal.

It provides more mechanical strength to the joint.

It seals the graft, including the exposed portion of the scion, and reduces the risk of the scion drying out.

Speaking of drying out, this year I am using brown, paper lunch bags. They reduce drying and raise the temperature slightly and speed the graft healing.

I have a wire stretched between posts at 4'. I put the wire cage around the newly grafted rootstock to protect it from deer. I tie the cage to the wire with five wraps of baling twine and then a square knot. The five wraps grips the support wire enough so the cage will not slide.

As a guy who has grafted more than my fair share of trees, and after talking to a dozen really good grafters, the biggest reasons for newbie's grafts failing is not poor carpentry. Rather, it is lack of good after-care.

Keep the rootstock well watered. Keep the weeds down. Peel sprouting buds off the rootstock. Don't let the scion dry out. Have a plan for wildlife like deer and birds that want to land on the healing scion.

Hat/tip CoyoteKen

That was great! Thanks. I learned a lot. Several things different than what I learned from my grandfather 55--60 years ago. I'll give your technique a try tomorrow on something I've been considering doing for a year now. What is the maximum length of a scion? Thanks again---ken

ReplyDeleteI agree with CoyoteKen- that was great!

ReplyDeleteThanks so much for sharing your expertise!