|

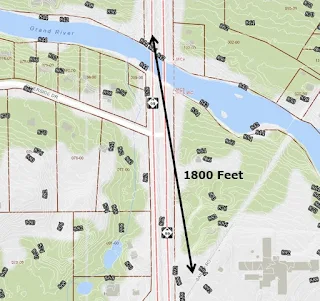

| M-99 bridge. You can click on the image to embiggen. |

The good news was that Donnie rotated up to the Columbia Road observation post. That put him only six miles away, close enough that they could train together and socialize. Donnie used to be in Quinn’s squad but was later promoted to Team Leader of Squad One. Donnie was leading the combined forces of Squad 1 and 2 into an ambush when Quinn was wounded. Donnie was able to salvage a blown operation through patience, skill and luck.

|

| Clockwise half-squad billeting in houses circled in red. Houses at the 860' elevation, same as M-99 roadbed. |

A couple of fighters on the clockwise half-squad were ace scavengers. There was never a shortage of high-end booze. All three of the “fighters” were snockered at 1 in the afternoon when Quinn rolled in.

It was a test of wills. Quinn demanded that they move their bivouac every night and that the bivouac site always be handy to the elevated plateau south-east of the bridge spans. The clockwise half squad saw no reason to desert the luxurious lodgings along the river west of the bridge.

It was very clear to Quinn that his survival depended on every team member doing their job: Right place, right time, right gear, right mindset. The clockwise boys were not cutting it.

If the clockwise crew thought Chernovsky or Gimp were going to say anything about the sudden profusion of black eyes, swollen noses and scuff-marks, well, they didn’t know Chernovsky and Gimp all that well.

It took a few days, but the clockwise crew finally rolled over. Quinn had no doubts that they would revert back to their lazy, sloppy ways as soon as they rotated to Waverly Road, but they would only have a week to settle in before Donnie rotated in and kicked their asses. Again.

Chernovsky and Gimp were much more aware of what was going on than any of the fighters realized.

Chernovsky was all about getting all of the fighters in-line with what Quinn was creating.

Gimp advised going slow. “Quinn's system is still a work in progress.” he informed Chernovsky. “We can roll-out what he is doing but we will have to redo it three times as he gets better at fitting the pieces together.”

Quinn’s crew was busy. Janelle dropped off a mortar tube and practice rounds of ammo. Quinn was extremely skeptical. The rounds were 14.1 ounce propane cylinders ballasted with water. The nose-cones were concrete and the nose-cones had 6” long probes sticking out of them. The mortars were 48” long pieces of 3” pipe. The mortar rounds did not have obdurating rings but relied on primitive “reed valves” to vent the air displaced when the rounds slid down the tube.

“You don’t have a lot of flexibility with this ammo.” Janelle apologized. “You have one powder charge. Setting up the tube at 60 degrees should get you almost exactly a quarter mile of range. Maximum range is at 45 degrees and is only a little bit more...maybe 500 yards.” *

“Why did you pick a quarter mile?” Quinn asked.

Janelle looked around the observation post. “Everything in Michigan was originally laid out in 40 acre parcels. They are a quarter mile on a side. There aren’t many places around here where you can’t stay out of sight and get within a quarter mile of your target.”

What Janelle was not telling him was that increased range equated to less accuracy and more powder per round. More powder per round meant the fighters would have less ammo to launch toward the enemy, exactly when it was harder to hit them.

At a quarter-pound of black powder per round, a maximum range of 500 yards was the equivalent of an 8”, adjustable wrench...the smallest size that offered a high degree of applicability.

Quinn tossed the “round” from one hand to the other. It did not feel like much mass. “What is going to be in this?” he asked.

“We are still working on that.” Janelle admitted.

“I am 95% sure that the live rounds will be this size, weight and powder charge. These will be close enough for you to pick some firing spots and lay the mortar in.” Janelle said.

“Firing spots?” Quinn said. “Are we going to get multiple mortars?” he asked, hardly daring to hope.

“Nope. Just one.” Janelle said. “But you need a primary site and a back-up.”

|

| Elevation profile from mortar site (left side of image) to target zone. |

Quinn called Janelle back the next day and told her that a quarter-mile of range just wasn't going to cut it.

Janelle sighed and said she would be on-site in a couple of hours.

"Why won't a quarter-mile work?" she asked as they stood on the site that Quinn had determined was the optimum site for the primary mortar installation.

"Because it is 600 yards to where an enemy convoy will stack-up as they try to breach the barricades." Quinn explained.

Janelle could see how the high, level site was a great place to set up a mortar. The cusp of the flat visually shielded the crew from the hostiles.

"Why don't you move closer?" Janelle asked as she pointed to another shelf that was closer to the bridge.

"No egress." Quinn said, not wasting words. "Egress" was a word he would not have used if you had paid him when he was in high school. Now the word rolled off his tongue with no effort because it was the single best word to explain why the flat shelf Janelle suggested was not acceptable.

Well, that and the fact that the mortar would still be more than a quarter mile from the target.

Janelle sighed. If you are going to ask for advice from an expert then it behooves you to give it ample consideration.

"So, how much do you absolutely need?" Janelle asked.

"1800 feet." Quinn replied.

"I will give you 2000 because you might be shooting into a headwind." Janelle announced. She had played this game before. Damned if she was going to re-figure the powder loading an infinite number of times.

It took 20% more powder but in the end even Janelle admitted it was the right thing to do. After consideration, she could see how a crew might need to shoot corner-to-corner across a 40 acre field and that is almost 1900 feet. Problems don't always fall square-to-grid.

*

Laying in and sighting in the mortar with the longer range ammo was incredibly time consuming until Miguel suggested they paint the practice rounds bright pink. After that, it was much easier to find.

Quinn came to the realization that it was better to over-shoot the bridge than to try to drop rounds right on top of it. That information occurred to him when he was sure they had lost the practice round the day there was a cross-wind. They found it in the two-feet deep water thirty feet east of the east span of the bridge. Quinn was 99% sure that a live round would not go off under water. And even if it did, it would have minimal effect on the enemy twenty feet above the water line.

Lobbing the rounds slightly past the bridge ensured the probe of the fuse would hit a surface that was hard enough to detonate the primer and guaranteed that it would be easy to find where the practice round landed.

Quinn kept notes on every round they send downrange. He figured that every degree of increased elevation between 60 degrees and 75 degrees brought the point-of-impact 50 feet closer to his launch point and an additional five degrees moved the impact 250 feet closer.

He wrote up a 3" by 5" cheat-sheet and attached it to the mortar tube.

*Nominal exit velocity of 260 feet-per-second yields those ballistics and an estimated 14 second hang-time for the 60 degree launch.

Next

Mortars are quite useful - but a royal pain to set up for repeatable use. Don't forget that a lack of fins reduces accuracy.

ReplyDeleteI have a registered 60mm mortar and it is really neat - when it works right. With a limited number of engineered rounds, recovery and reloading is required. My home made rounds haven't worked well yet.

God bless Texas.

Delete