People look at the lush jungles and cannot believe that the soils in wet, tropical areas are extremely infertile. It is counter-intuitive to believe that almost all of the nutrients are captured in the living plants and animals and almost none of those nutrients are in the soil.

In tropical regions, organic matter that hits the surface is very quickly broken down by termites, fungi and bacteria. Feces is scavenged by ants and beetles. The humidity and temperatures make that happen in a matter of hours or days.

Tree roots in jungles are typically very close to the surface and very finely divided as there is a life-and-death race to capture those newly released nutrients before another neighbor does. The tree that is slow to capture those nutrients is over-topped by its neighbors and languishes in their shade.

That compares to dry grasslands where dead roots decay-in-place and captured nutrients accumulate over the centuries. Cool, temperate regions also lack the super-aggressive decay mechanisms seen in the tropics and can accumulate nutrients in the soil.

Since science mostly evolved in temperate Europe and North America, we tend to think all soils are like, or should be like, the soils of Geisenheim, East Malling, Saint-Aubin or Champaign or Ithaca.

The soils of Tennessee, in particular the soils of the Cumberland Plateau are more like tropical soils than they are like the soils of central Illinois.

N-P-K

The three macro-nutrients for plant growth are Nitrogen, Phosphorous and Potassium. There are several important "minor" nutrients like calcium, magnesium and sulfur.

Nitrates are leached from tropical soil in a matter of months and years.

Potassium is very soluble and is leached out of tropical soil in years-to-decades.

Calcium and magnesium carbonates like limestone and dolomite, and calcium sulfate (gypsum) and most phosphates dissolved out of tropical soils in a matter of decades-to-centuries.

Silica (sand) also dissolves, but more slowly. Little known fact, rice stubble and chaff is very rich in silica and rice-straw can be used to make silicon carbide whiskers.

That leaves clay.

Over time, the clay also changes. Young clay is slippery/slidey because cations of sodium and potassium act like ball-bearings between the flat clay particles. Imagine the shingles torn off of a roof and tossed to the ground. The shingles tend to lie flat-to-flat. That is what clay particles look like. The cations nest between the shingles, held there by ionic attraction. Water fluffs-up the shingles and lets them flow freely.

Over time, water leaches out the sodium and potassium ions and the clay become blockier at the molecular level.

The blockier clays (like kaolin) are generally preferred for pottery over the shingle-like clays (like bentonite and montmorillonites) while the shingle-like clays are preferred for kitty-litter and for sealing bore-holes and the bottoms of ponds.

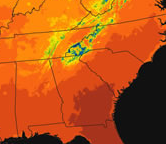

The mid-South...like eastern-Tennessee are directly down-range of the vast amounts of water that evaporate from the Gulf of Mexico. The centrifugal action of the earth spinning causes dry, dense air to move toward the equator down the spine of Mexico and displace the less dense, wet air and allow it to move north toward the poles.

Because the air has eastward momentum due to be farther from the axis the earth spins around, the storm tracks arch eastward as they head north on the weather conveyor belt where they smash into the Cumberland Plateau. As Larson succinctly stated, "Bummer of a birthmark, Hal".

Another factor that comes into play. is that the Cumberland Plateau rises approximately 1000 feet above land to the west. Especially in late-summer and early-to-mid fall when the surface temperatures of the Gulf are hottest, the Cumberland Plateau are the bowling pins and storm tracks are the bowling ball.

They get a lot of rain.

More recent history

Before white settlers showed up, the forests of the Cumberland Plateau burned every six-to-eight years.

Settlers between 1750-and-1929 bent the land to the plow and hoof, girdling and burning to clear the land.

The ashes from that burning were the only amendment to the soil.

The low pH and dearth of potassium and phosphorous limited the growth of clovers and other legumes that could have naturally enriched the soil.

During the Depression, the marginal areas of the mid-South were depopulated of farmers. They moved to Detroit or to TVA projects in the valleys.

The trees grew back as second-growth forests.

Is it hopeless?

Humor me and let me start with a story.

A young fellow was driving in Wyoming during a white-out blizzard. He drove for fifty miles and could barely see the road. Finally, he spotted a gas-station/convenience-store beside the road and pulled off.

Going into the store, the young flatlanders complained to the proprietor "I thought you didn't get a lot of snow in this part of Wyoming."

The proprietor responded "We don't"

"Well what about that?" the young fellow objected, pointing outside.

The proprietor shrugged. "We don't get a lot of snow here, but we get a hellova lot of mileage out of the snow we do get."

Point being, one inch of snow can look like a lot if it is dry and the wind picks it up and blows it at 30mph.

The story applies to Sig and Blain's challenges at Copperhead Cove in two ways. They need SOME fertility just like Wyoming needed an inch of snow. The second point is they can make SOME fertility work as long as they rapidly cycle it back into growing plants just like the tropical forest does.

That cloud of blowing snow probably didn't extend more than fifty feet in elevation.

The key to rapidly cycling nutrients is to spread it thin and to spread it on growing plants.

Even though the "bump" in crop yields will be primarily due to the nitrogen in the chicken-shit and bedding, the long-term benefits will be the phosphorous and potassium that will allow red clover to germinate and grow in future years/decades thereby making fallow-years far more effective at creating fertility.

Minor issues

One minor issue with the way the residents of Copperhead Cove are managing their fertility is that potassium is mostly excreted in the urine while phosphorous is mostly excreted in the poop.

Long-term, throwing the poop from the pasture into the garden will result in phosphorous migrating from the pasture to the tilled area. The tilled areas will not be able to exploit the increased phosphorous because it will not be balanced by the necessary amount of potassium.

Similarly, the potassium which is cheerfully cycling in the pasture will not be able to stimulate clover growth because of the growing lack of phosphorous.

The productivity of both areas will diminish (especially the pasture) even though there is NO NET OUTFLOW of nutrients. The problem is that the nutrients are segregating.

The exception to this general flow will be the garden plots closest to the buildings which will get dressed with wood-ash which is rich in potassium. Those plots will get both manure (nitrogen and phosphorous) and wood-ash (potassium). A person who does not walk all of the "fields" but only looks at the ones closest to the buildings will think everything is peachy-keen.

One "fix" that can happen is when the small-holder supplements the cows on the pasture with corn-stalks in the winter and/or corn (grain) in the summer when their milk production sags as they graze the least fertile parts of the pasture. That returns phosphorous to the pasture as long as all poop is not collected and put on the tilled areas.

I'm doing what I can to coax food from a suburban lot in coastal Florida. The local substrate is a fine sand, acidic. The soil survey optimistically describes my particular sand patch as 'loamy," but it drains very rapidly and grows yellow pine and live oak just fine. The climate is hot in the summer and generally warm with occasional late frosts that can destroy young plants or tropical specimens that might otherwise live. The front yard gets die-rect sun until early afternoon, the back is screened with a high oak canopy whose coverage moderates the harsh afternoon sun and occasional frosts.

ReplyDeleteI've been establishing something like a permaculture "food forest" in the sun-blasted front yard, arranged to look like landscaping as much as low-effort, relatively high-volume, year-after-year food production. Several "island beds" are anchored with deliberately stunted pomes and stone fruit trees, creating an overstory for berry bushes, figs, and the like. Interplanting of various colorful wildflowers attracts pollinators and softens the look. "Green manure" plants and pest repellent onions and herbs fill any gaps. The annual garden beds, the high-calorie root crops, and the tropical stuff are in back where there is more shelter. This is also where I compost. I bring home a potato box or two (20 to 100 pounds) of restaurant waste every night I work, religiously, for about three years now. I also get wood ash, charcoal, and boiled-out bones to bury. The difference in fertility, growing ease, and general plant happiness due to those constant inputs is remarkable.

My patch of sand is very deficient in some respects, and the more I've learned in my personal gardening saga the more interesting it is to read about. Your detailed interweaving of the complexities of fertility into the Cumberland story deepens the narrative and personalizes Sig's concerns for his people. It's motivating, too- I'll be taking a test kit to the basic dirt and selected enriched areas of my own plot tomorrow. Soil chemistry needs to be quantified, even if only at a basic level.

I was very impressed by how well Yaupon grew around Pensacola. Yaupon is one of the few plants native to North America that produces caffeine!!!

DeleteFrom what I read, nematodes are a struggle in Florida. This guy (https://floridafruitgeek.com/2020/06/11/some-of-the-best-mulberry-cultivars-need-nematode-resistant-rootstocks-in-florida/) seems to have a handle on growing fruits in central Florida.

Thanks for commenting!

Ilex vomitoria is very happy around here, but I only have one on the property so far. It's tasty brewed up and it WILL wake you up. Nematodes may eventually be a concern due to the limited space I have and the number of mulberries and nightshades in the space; my most common "weeds" are peppers and tomatoes that volunteer out of the kitchen compost.

DeleteAnd Michael Bloomberg, that pompous twit, says you don't have to be smart to be a farmer...

ReplyDeleteIn our hilly section of New Hampshire, the soil survey says our soil is "loamy" but it sure has a lot of rocks, from baseball size to bus-sized. Nearly all of our farmed land is pasture. We raise sheep and pigs on it. The sheep manure takes forever to break down but the pig stuff is powerful fertilizer. To balance and break down the manure we range flocks of chickens and turkeys in 25'x25' netting enclosures which are moved every day, following the sheep as they rotate around their own daily paddocks - intensive rotational grazing. Our biggest problem area is the 3000sf vegetable garden which is heavily compacted soil at a low spot that floods too easily. We are trying to build up beds with compost so that they will drain better. I don't really know what I'm doing but it gets a little better every year.

Farming on flat, fertile fields might be reduced to a formula and stuffed into a computer with GPS.

DeleteGardening is a different ballgame.

Sort of like the difference between golf and rugby. Both games involve getting a ball to a specific location some distance away...but there are a lot of differences between the two.

Nematodes are a problem here in east central coastal FL. I garden raised beds. I'm here ten years and still learning what I can grow successfully after transitioning from northern New England. Huge change from clay to sand and short season to year-round. I am in the middle of an experiment mixing french marigolds in my nematode susceptible plantings (okra for instance). My other nemesis is fire ants.

ReplyDeleteThere are some okra varieties with moderate resistance to root nematodes. Arka Anamika is one of them. Link: https://www.scielo.br/j/brag/a/HKhQ3npT6CbsfSkcwqSPM4H/?lang=en#ModalTablet01

DeletePossible source of seeds here: https://www.kattulafamilyfarms.com/product/dark-green-okra-arka-anamika/197?cp=true&sa=false&sbp=false&q=false&category_id=4

Thank you!

DeleteRotating crops and livestock (sheep, goats, hogs) are a great way to avoid such problems.

ReplyDeleteSeems one trick would be let all the un-harvested garden crops lay on the ground, and purchase a couple young hogs which they would over-winter on the plot. Their rooting action dug the soil, their dung and urine enriched it, and they stayed happy fidgeting around looking for root vegetables left behind.

By Spring time the dirt was all tore up and the hogs harvesting age.

buttresses good info

ReplyDeleteI hope to remember it and look for it.